2. Exit

Saying good-bye to the known world

Buenos Aires deserves its own story. The place is swirling and cosmopolitan and erotic and chaotic, and it’s all true and fascinating — and all of that action happens two thousand miles north of where this shot was taken.

Yesterday, I sat in a cafe, nursing yet another dulce de leche granizado, and the very next day…

Here, at the base of the Andes range, Earth seemed to be both finite and infinite. Finite: the Americas end here. These severe stones are the last rocks you get before the continent ends. And infinite: slopes and ravines formed so long ago they seem ageless. Tierra is a grandiose place.

While it was remote, it was also far from desolate. Industrious beavers left their handiwork everywhere, having dammed up whatever stream they could find. Song-birds fluttered. Fish congregated. Thick grasses, dense tree cover, rocky beaches and mucky swamps: so much motion in so many different scales! Including the human scale. Ushuaia is a hip little outpost, forming the base camp for countless adventures like mine. Ushuaia has cafes and pubs and boutiques and streetlights and pets and signs that warn you not merely about icy roads, but for the real peril: penguins crossing those icy streets. Use care! Pinguinos get the right of way!

(As they should!)

Ultimately, I didn’t really get to explore Tierra or the broader Patagonia region. As unfortunate as that is, 1) I will be back, and 2) I say this without being dismissive, but those were always secondary. I had an agenda. And I had a boat to catch.

The Boat.

I will dedicate an entire story to The Boat, but for now, suffice it to say that it was docked in Ushuaia and we could not dawdle there. We had to make a carefully choreographed trip through the civilized waters of the Beagle channel, leading us to a peculiar stretch of the South Atlantic that is, to be charitable, choppy.

Champagne toasts. Individual handshakes from our Captain.

The westbound swim across the Beagle was quiet — a glide — an elegant movement that had little feeling of movement. No sense that we were heading toward a unique body of water. Maybe this calm was a deception. Maybe it was even an act of mercy, allowing us seafarers some time to get used to the noises of boat-life, the groans and creaks and rattles — allowing us to understand the feel of water under your feet.

Our Boat was extraordinary. In my opinion, Le Lyrial is artwork that also happens to be a sailing machine.

But even on such an advanced ship, sailing is strange. It does not feel like driving or flying. If anything, it feels like turbocharged surfing. You are, in a sense, riding waves, hydroplaning with them, pushing through them at times, conquering them by taking them bow-first — and at other times, you are simply at their mercy.

We cruised flat and steady through the Beagle, wondering if or, more accurately, when the “mercy” part would begin.

(The Beagle Channel is named after the British ship that explored these waters in the early 1820s: the HMS Beagle. The Beagle explored Australia, too, but is probably most famous for one of its scientific passengers. Charles Darwin.)

The last signs of known-Earth faded to dark shapes, and then simply vanished, slipping away, under the horizon —

No fireworks,

Not even a signpost,

It’s just

Gone.

It is disorienting and even disturbing to watch land simply vanish. At that point, you become acutely aware that you have assumed that the people guiding the boat — The Captain and Crew — actually have the extremely sophisticated skills they say they have. You have assumed that they have a plan, that their plan is a smart one, and that they can actually execute this plan. There was never any reason to doubt this, of course. But the very presence of these assumptions becomes much more acute when land is simply

Gone.

Slowly… the waters started to pulse.

As much as I watched the Beagle disappear, I also felt it disappear. From a dead calm, little disturbances in pitch, roll and yaw emerged, shifting under our feet, throwing frothy tips of salt-spray up against windowsills that had been dry before.

The ocean was starting to have its say, and this brings me to The Drake.

Every day on board we were given a set of briefings, concerning what we had done that day and what we were hoping to accomplish tomorrow. Our first lesson was that respect for the weather and respect for wildlife would dictate absolutely everything about our agenda.

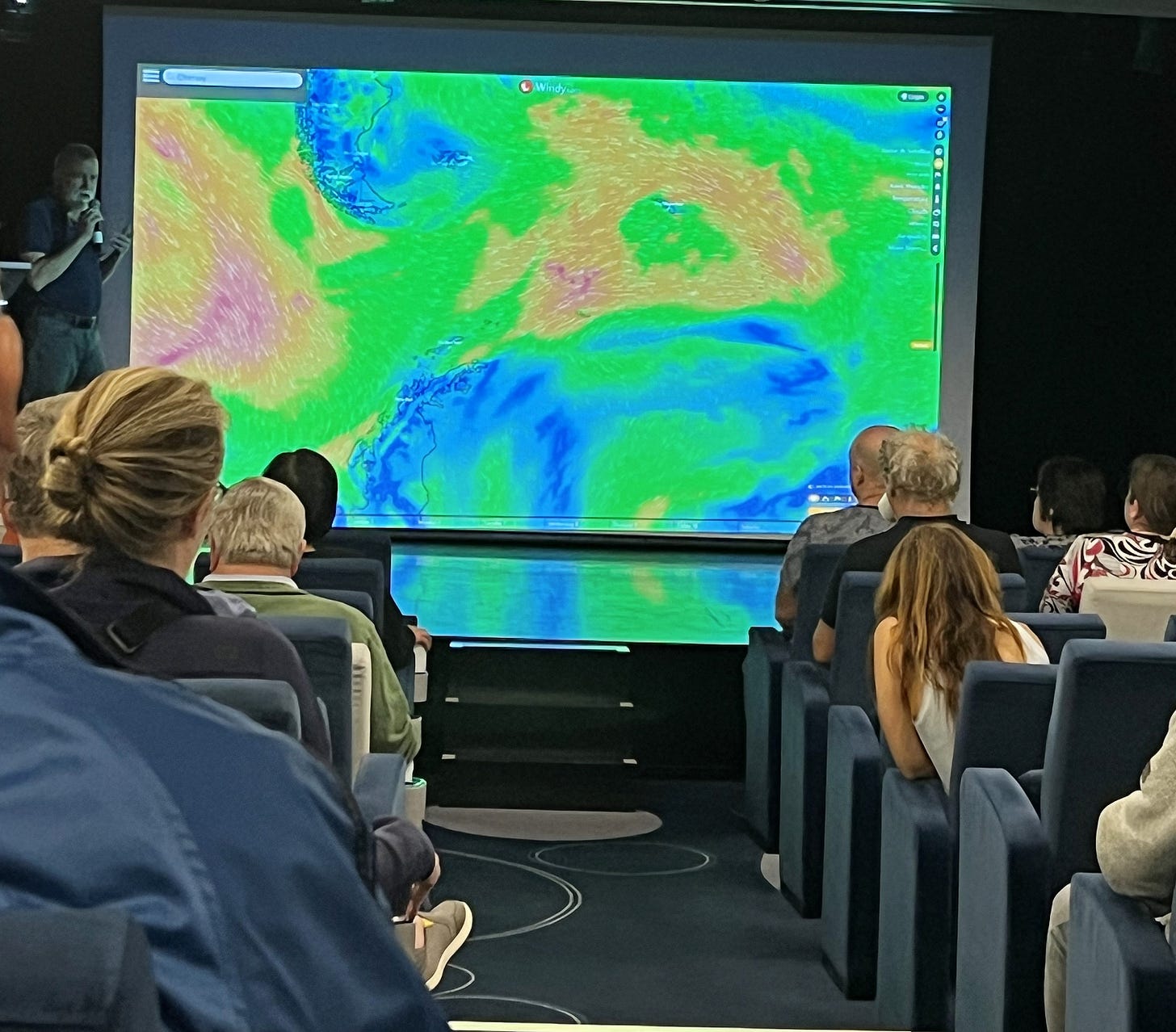

Our second lesson was about our journey south, and contained the following heat map:

Tierra del Fuego is the spindly blue bit up top. The Antarctic Peninsula is the blue finger at the bottom.

Green: mild weather, gentle swell. Red: swirling storms, furious waters. Green: relative calm. Red: skyscrapers of water folding over your boat.

A bit of science about The Drake. Specifically: why is it such an extreme environment? There are a few reasons.

First, we’ve got the Antarctic Circumpolar Current to contend with.

This current moves at least billions of cubic meters of thick, frigid, deep-ocean water, whipping itself around the bottom of the world, uninterrupted. Between 50-ish and 60-ish degrees south latitude, there are barely even isolated islands. The French Southern and Antarctic Lands — Crozet and Kergulen islands — are among the most remote places on Earth at 46 and 49 degrees south latitude. And there’s the fur seal and penguin breeding grounds on South Georgia island, lying at 54 degrees south latitude. And that’s really it. The Circumpolar Current has Earth almost entirely to itself.

So there’s a massive, sweeping current — and then there’s wind.

The Drake Passage is the narrowest gap between Antarctica and the rest of the planet, which means that this gap also acts a funnel for both current and wind. Surface winds and storms coalesce, directing their formidable energy into waters that already have a lot of chaotic energy sloshing around. Everything gets amplified; everything gets big and weird.

The Captain told us our trip down would be as calm as it can get on the Drake. Our guides agreed. I’ll say this: on the way home, we got a snarling Drake, and I have no trouble believing that forty-foot swells and beyond are possible, even probable at times. There is no doubt our trip down was as gentle as possible.

As a practical matter, I never got seasick. And for this, I have a heavy debt to scopolamine. If you plan to make this trip, you must have them.

(The Antarctic Circumpolar Current is an essential part of the global ecosystem. Among other things, it gives birth to plankton, which feeds a shrimp-like critter known as krill, which in turn is the core food for dozens of species, from virtually every whale species to dozens of birds.)

Hour after hour of this:

The dull churn of two azipods, pulling us rope-like through sloshing slates of dense, deep blue water…

Hour after hour, wondering:

What is underneath this boat? What is around us? Is anything here? How alone are we? What is this strange blue void, this no-man’s-land? And if we are alone now, how much more alone will we get when we get to The Place?

I’m cheating here a little — this shot is from our return voyage — but it was taken in the middle of the Drake.

This is a southern royal albatross.

An entire body built to use windshear itself as the propulsion, working in cycles:

Up: building potential —

Down: diving, creating speed, covering distance —

Riding this way for thousands of miles:

Up: flexed wings, capturing the wind

Down: releasing energy, swooping to the ocean’s frothing face —

And then waiting, and timing the shear, so those massive wings lift the bird once more.

And to think I believed the ocean was a blue void, or a blank space, a proverbial middle of nowhere. Middle of nowhere — to whom? This is an albatross’ home. This is how they live their fifty or sixty or seventy years; by air-sailing over thousands of miles water that humans see rarely, if ever. Empty? To whom? Not to a whale, cruising north and south in search of food or a place to give birth. These dense slabs of water are not recognizable to me as a home, but that doesn’t make them empty; life is everywhere out there.

Churning motors. Cycles of birdflight. Gusts of growling wind. And silence.

Waiting and wondering —

Where are we?

And then, the temperature on deck dropped, and the days grew really, really long, and then the rolling Drake drew down into a tamer pulsing, and there was a heavy mist, a mist that seemed to cleave the sky in half, and

It emerged.

Wonderful to travel along with you.

You have such a way with words...I feel like I was right there with you. Your photography, in conjunction with your writing, tell an amazing story of your journey. I can't wait for more...